Lexicon

A is for ACoP – understanding the role of approved codes of practice. A whole paragraph has been missed at the start of this one:

Approved Codes of Practice (ACoPs) published by the UK HSE are described by in health and safety text books as having a “quasi-legal status” (for example, Stranks 2006, Hughes and Ferrett 2011). The HSE never use this term, instead explaining that each ACoP has “special legal status. If you are prosecuted for breach of health and safety law, and it is proved that you have not followed the relevant provisions of the Code, a court will find you at fault, unless you can show that you have complied with the law in some other way.

The article goes on to explain how this is a prosecution tool, and HS professionals could become unstuck if they think it’s a tool for the defence.

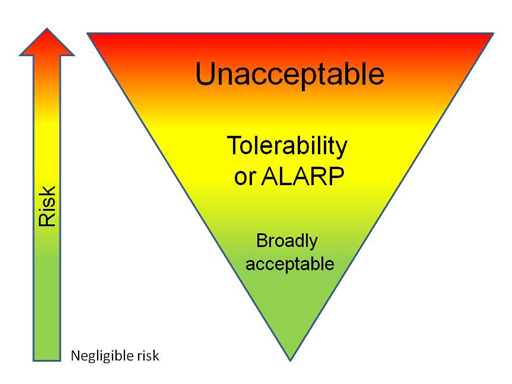

A is for ALARP – the legal concept, as low as reasonably practicable, its origins and application..

The boundaries between acceptable, ALARP and unacceptable aren't as clear as we sometimes pretend

B is for Behavioural safety – the ABC of behaviour theory, and why workers are more complex.

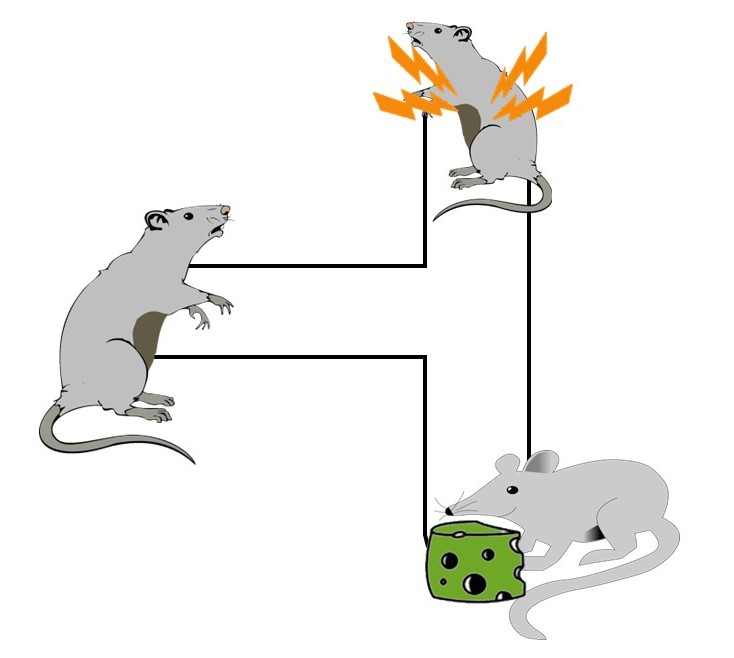

This is one that has been used in the IOSH Blueprint. I had ideas for a much longer article on this topic, and I’ve already drafted some models to support this (as well as an illustration of mice in a maze, used in presentations but not so far in an article). Let me know if this is something you’d want to read.

B is for Benchmarking – explaining how to measure your health and safety performance against others.

This is also used in IOSH Blueprint.

Missing first line on the IOSH Magazine website:

In the Middle Ages cobblers marked their workbench with the size of a customer’s foot, so that whilst working on a new shoe they could check it against the mark on their bench – or against the benchmark

Behavioural safety treats workers like mice in a too simple maze

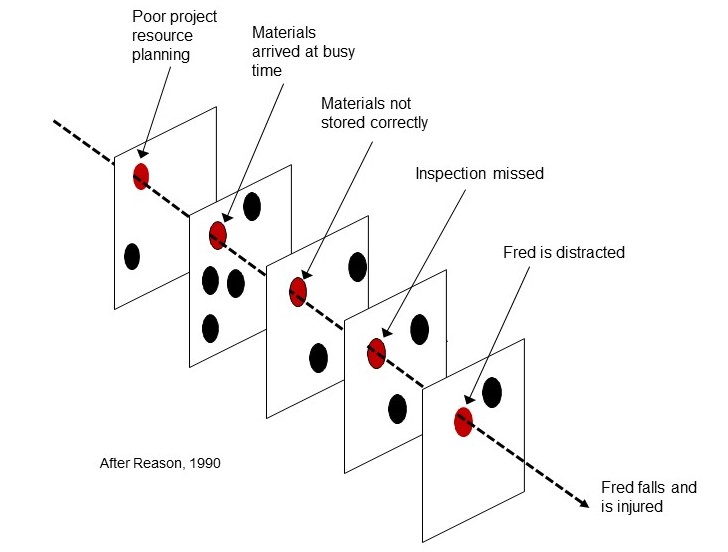

C is for Causality – Heinrich, Bird and Reason all get a mention here. My original text doesn’t claim Bird as the inventor of the accident triangle, and the first para (which is essential to understanding U is for Underlying causes too) reads:

As Fred walks to his work area on the building site, his phone rings. He knows that mobile phones should be used only in the mess room, but he looks to see who is calling, and his toes catch the edge of some building materials left on the path. He falls, injuring himself. What is the cause of the accident?

I didn’t use this illustration in the article, but I found it a useful thinking aid to work through the ideas. It is based on James Reason’s Swiss Cheese model (which deserves an article of its own) and shows how several things have to go wrong for the accident to occur. Some might have gone wrong at other times (illustrated by the black holes) but only when all the holes line up (the red holes) do you get an accident. So which of the holes “caused” the accident?

Swiss Cheese model illustrating Fred's fall (After James Reason, 1990)

C is for Common sense – one of the articles I refer people to most often. TLDR: Anyone who believes that they have common sense has simply forgotten who taught them what they know. The missing first sentence is:

“Common sense” implies that there is some native, in-built sense of what needs to be done, present in all of us at birth.

In 2023 there was a longer article in IOSH Magazine on Common sense, in which my original advice was quoted by IOSH head of health and safety policy. The longer article is no longer available, read my LinkedIn blog for a comparison of the articles.

Common sense is what you know but you've forgotten how you learned it

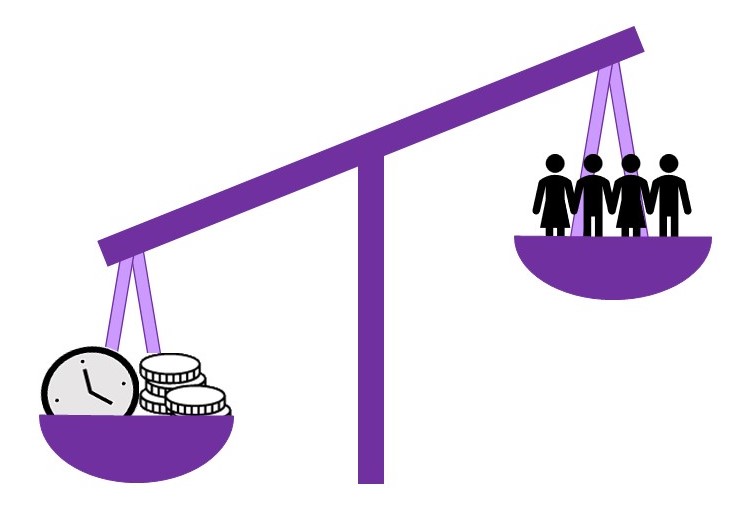

D is for Disproportion

Missing opener:

In determining whether a safety measure is required the HSE define the proportion factor as the ratio of sacrifice (the cost of the safety measure in money, time and trouble) to the benefits of that measure in terms of risk reduction. In traditional business practice, a cost-benefit analysis …

Every time this article comes up in conversation I am reminded that I need to upload my two articles on calculating the value of a life (VOLY) or the value of a prevented fatality (VPF).

D is for Duty of care

Used in IOSH Blueprint.

Missing opener on the IOSH Magazine website:

In civil law a person can seek compensation where they can show that they were injured by negligence or by a breach of statutory duty, and that the defendant owed a duty of care. The question of to whom we own a duty of care …

It's not enough to spend 'just' enough

E is for Ergonomics

Missing paragraph:

Ask the average office worker what an ergonomist does, and they will probably tell you they adjust chair heights and computer screens. In the nuclear industry I heard ergonomists described as “knobologists” because the perception was that their main job was to decide on the position of knobs, buttons and lights in a control room. These examples suggest that ergonomics is not as well understood as it should be.

E is for ETTO

Missing paragraph:

ETTO is an important concept in Hollnagel’s Safety II concept, which in turn influenced the Safety Differently approach described by Sidney Dekker and popularised by John Green. And yet, whilst a just culture, the curious why and hindsight bias have become ideas to talk about, ETTO doesn’t get much coverage.

Modern human factors must match psychological capabilities to tasks not just physical

F is for Foreseeability

Missing sentences:

At the start of the alphabet, we looked at ALARP – the idea that risks should be reduced As Low As Reasonably Practicable. Foreseeability plays a key role in determining what is reasonably practicable. It is not, for example reasonably practicable to put controls in place to prevent an alien invasion of your work site, since this is not a foreseeable event. As the judge in a 1932 civil case put it, there is no need to protect against “fantastic possibilities” such as Mr Harcourt-Rivington’s normally docile terrier smashing the window of a car, causing an eye injury to Mr Fardon, who happened to be walking past at the time.

F is for FRAM

Missing / changed text:

Last month in E is for ETTO we mentioned how a technique called FRAM could support people in making the right efficiency-time trade-off to prevent accidents. So what is FRAM?

Traditional safety techniques, whether for assessing risk or for investigating accidents, assume a causal chain of events – driving the forklift truck too fast caused the driver to hit the pedestrian, which caused the injury.

There’s also chunks of text missing in the middle, such that the mention of “Rawlinson” at the end makes no sense! Just above the large quote the section on the Millenium bridge ends:

Despite a long history of engineering knowledge, those designing the bridge did not foresee the effects of crowds of people walking on the bridge.

Before the unattributed quote, the sentence which made the attribution clear was omitted:

Helen Rawlinson, Managing Director of consultancy and training organisation, Art of Work. explains some of the successes they’ve had with FRAM.

Foreseeability needs to go beyond the obvious, but not the 'fantastic'

G is for Gross Negligence manslaughter

Missing paragraph and link updated in 2023:

On 31 July 2018 the Sentencing Council for England and Wales published a new guideline for manslaughter applicable to sentences delivered from 1 November. Although not specific to health and safety offences, the guideline is anticipated to have an impact on the type of sentences received by individuals deemed responsible for gross negligence manslaughter following fatal accidents at work. A previous article in IOSH Magazine outlined the starting points and ranges for each level of culpability, from one year for the lowest level of culpability to 18 years for the highest culpability level with maximum aggravating factors.

G is for Guilt

Missing sentence:

When Burglar-Bill is arrested, Bill knows he is guilty, but the legal system starts with the assumption of his innocence, and the courts have to decide whether there is sufficient evidence of guilt to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt.

Burglar-Bill knows he is guilty; employers often won't know immediately

H is for Hawthorne effect

Missing sentences:

The Hawthorne effect is often defined as the tendency for people to perform better because they are being observed, with Wikipedia and others even using the synonym “observer effect.” This is a massive oversimplification of the original study, which can lead to mistakes in how organisations try to change the safety behaviour of their staff.

H is for Hazard

Missing sentences:

Consider a typical risk assessment template, such as that provided on the HSE website. The first column asks the assessor to answer the question “What are the hazards?” The HSE define a hazard as “anything that may cause harm” while IOSH and NEBOSH refer to “something with the potential to cause harm.”

In this article I go on to have a dig at the HSE for not using their own definition when coming up with examples of hazards for their sample risk assessments. This is a theme developed further in the first two chapters of my book.

Was it lighting, being watched or being cared about that change behaviour at the Hawthorne Works?

I is for Incident

Missing introduction:

For a term so widely used, you might think there would be a legal definition. Unhelpfully RIDDOR provides the circular explanation that a reportable incident is “an incident giving rise to a notification or reporting requirement under these Regulations”. There are some clues …

I is for Interested party

Missing introduction:

In ISO 45001 the term ‘interested party’ is the term used in preference to the admitted synonym ‘stakeholder’ that many readers might be more familiar with. ‘Interested party’ is defined in ISO 45001 (and in the high-level ISO management standard, Annex SL) as a ‘person or organization that can affect, be affected by, or perceive itself to be affected by a decision or activity.’

The ISO definition of 'Interested party' seems circular

J is for Job Safety Analysis

Used in IOSH Blueprint (but note updated text below)

Missing introduction (which I’ve updated as the original HSE link has changed):

According to the UK HSE, Step 1 of a risk assessment is to identify the hazards. The advice is ‘Look around your workplace and think about what may cause harm (these are called hazards).’ This “I spy” approach will inevitably miss some hazards, such as those created by routine work, maintenance or emergency procedures.

J is for Just culture

Used in IOSH Blueprint (but note the original reference to James Reason’s book below).

Missing introduction on the IOSH Magazine website:

In his 1997 book “Managing the Risks of Organisational Accidents” James Reason described a Just Culture as “an atmosphere of trust in which people are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but in which they are also clear about where the line must be drawn between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour.”

Is justice blind? Or does a just culture need to look carefully at who has been harmed and who can provide the resources they need?

K is for Kanban

Used in IOSH Blueprint

Missing introduction on the IOSH Magazine website:

If you have come across Kanban, it is probably either in lean manufacturing, where it started, or in software engineering, where it has been adopted with enthusiasm as an agile technique. It could, however, be a valuable tool when applied to occupational safety and health.

K is for Knowledge

Missing introduction:

The Management of Health and Safety at Work (MHSW) Regulations tell us that someone is competent where they have “sufficient training and experience or knowledge and other qualities” to assist with the measures needed to comply with relevant health, safety and fire legislation, and to respond in cases of “serious and imminent danger”.

See also my longer article What is: competence? for an illustration of how knowledge, skills and training really map onto competence,

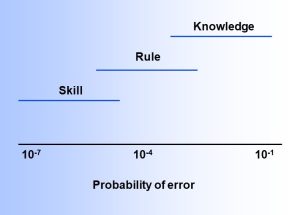

S is for SRK might also be of interest.

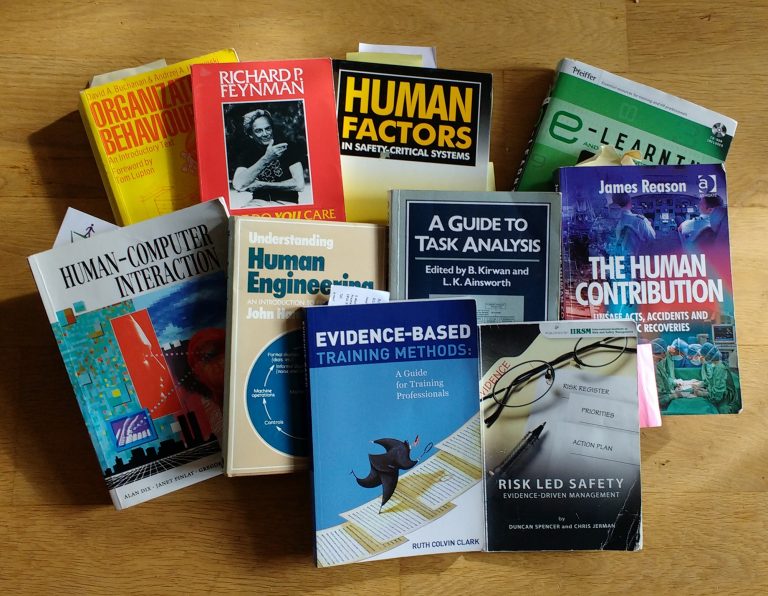

Not all knowledge comes from books

L is for Latent

Missing introduction:

The word “latent” is an adjective describing something that lies dormant or hidden, until the circumstances are suitable for it to manifest itself. The noun “latency” refers to either the state of having something dormant, or of the period of time before the manifestation is likely.

There wasn’t sufficient space in the original article to explain Reason and Hollnagel’s use of the term ‘pathogen’ to describe something seeded into a system during design, which is not necessarily a mistake, but that leaves a latent condition which is a contributor to a future accident.

L is for Leadership (in health and safety)

Missing introduction, updated in 2023 with a new reference to the HSE website, as the original quote is no longer available:

The UK HSE tells us that ‘Board members who do not show leadership in [health and safety] are failing in their duty as directors and their moral duty, and are damaging their organisation’. This is backed up by research summarised by Sharon Clarke (2013) and by accident investigations. In the inquiry report into the rail accident at Ladbroke Grove in 1999, Lord Cullen supports the belief that ‘the first priority for a successful safety culture is leadership.’

Note that several of the other references on the IOSH Magazine website version of this article are out-of-date. Let me know if you’d like to sponsor an updated summary of this topic.

Is latency like a pathogen, waiting for the right conditions to grow?

M is for Method statement

The introduction to this needs a little more explanation. The HSE has published multiple versions of a short guide originally called “Five steps to risk assessment.” The first chapter of my book attempts to explain this! There was a draft version in 2016 which was referred to in the original article, in the missing opening paragraph. The draft was never issued, and instead the HSE revised its website. Again, see the book for more details of why I think this is inadequate.

The RSSB link on the IOSH Magazine website no longer works – you can access the report on the RSSB site if you register, but be aware it is now quite old.

The following is a re-written introduction which takes account of these changes:

The UK HSE explains that a method statement ‘describes in a logical sequence exactly how a job is to be carried out in a way that secures health and safety and includes all the control measures.’

In a draft document on risk assessment in 2016, the HSE suggested that more reliance might be placed on documents such as method statements, in preference to duplicating content in overly detailed risk assessment documents. The content and role of the method statement is therefore worthy of further consideration.

A method statement is different from…

M is for Mindfulness

Used in IOSH Blueprint.

Missing introduction on the IOSH Magazine website:

When there is an emergency, our natural flight and fight response can result in poor decision-making. The traditional solution to this problem has been emergency drills – to make our instinctive reaction to the fire alarm or other emergency the “right” one. The worker hears the bell and evacuates. The firefighter sees a fire and tackles it. However, such a drill and practice approach doesn’t help when the unexpected is encountered, when the situation is constantly changing and a different plan is needed.

N is for Near miss – why it’s so difficult to define what you need reported.

See also an updated version of my longer article from HSW Magazine What is a near miss? – one of my most plagiarised articles!

Missing introduction:

The UK HSE defines a near-miss as “an event that, while not causing harm, has the potential to cause injury or ill health”. Some near-misses – such as those involving pressure vessels, lifting equipment and explosives that count as dangerous occurrences under the Reporting of Incidents, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR) – must be reported to the HSE, but the HSE encourage internal recording of and investigation into “non-reportable near-misses.”

N is for non-ionising radiation

Missing introduction:

Two types of radiation can be identified as a health hazard: ionising and non-ionising. The first includes the high-energy end of the

electromagnetic spectrum (such as X-rays and gamma rays) as well as particle radiation (such as the alpha and beta particles emitted by radioactive sources). Non-ionising radiation describes the middle and lower energy regions of the spectrum. In the mid-range, optical radiation includes ultraviolet (UV), visible and infrared, and in the lower range electromagnetic fields (EMFs) include those arising from power cables, microwaves and radio sources.

Here is a direct link to the HSE guidance HSG281, Electromagnetic fields at work

O for Observation

Used in IOSH Blueprint.

Missing introduction on IOSH Magazine website:

How many stairs are there in your house? Unless you live in a bungalow, you probably don’t know the answer to this question – you ascend and descend them every day, but you have never really observed them. It didn’t seem important.

Walk down the street, and there is so much going on. If you had to pay attention to everything …

O is for OHS standards – benefits and pitfalls of applying ISO and BS standards.

Comparing what is on the IOSH Magazine website with my draft, I’m guessing the introduction was cut short, so this probably includes text not in the printed version. However, we have plenty of space here, so you can have the original introduction:

Standardization (using the BSI spelling) was a key element of the industrial revolution. In the 18th century, tasks that were

previously done by skilled craftsmen could be done by less skilled people using new inventions such as the screw-cutting lathe to produce standardized tools and materials. The first customer of Whitworth’s standardized screw was the Woolwich Arsenal, and military purposes continued to encourage standardization. Guns made by skilled craftsmen varied in size, such that if you had two damaged guns in a war zone, you couldn’t use parts from one to repair the other. In the early 1800s Eli Whitney was able to provide the US Government with 10,000 standardized guns, all with interchangeable parts.

You might also be interested to see the more cynical ending I originally proposed for the article:

Perhaps the inherent contradiction of a group of people whose life work is to protect health and safety constrained by a framework with its origins in the military, in cost-reduction and in de-skilling is just too great.

Since its introduction I have occasionally seen ISO 45001 used well, as a tool to tweak a health and safety management system that was already going in the right direction. I’ve also seen it misused, for example with an organisation getting accreditation for an office building, and using it to imply its construction work is covered. Or I’ve been invited to a bidding war with other consultants who are prepared to sell a conformant system in three months, without any need for the client to change how they do things.

Can you train people to observe better? And the importance of magic!

P is for Perception of risk

Used in IOSH Blueprint.

Missing introduction on the IOSH Magazine website:

As Psychologist Paul Slovic states at the beginning of his 1987 Science paper on risk perception “The ability to sense and avoid harmful environmental conditions is necessary for the survival of all living organisms.” Similarly, getting people to sense and avoid harm at work is a necessary part of health and safety management.

P is for Probable

Missing introduction:

The probability of getting a head when you toss a fair coin is ½ – that is, one chance of a head divided by two possible outcomes. This can be written as a fraction, as the number 0.5 (where 1 equals certainty) or as a percentage, 50%. Similarly, most people will understand that by the same process, if you throw a six-sided die, the probability of a six is 1/6 (around 17%). However, when a colleague says that the chance of someone falling from a ladder is ‘probable‘ or its casual synonym, ‘likely’ would any two people agree what this means?

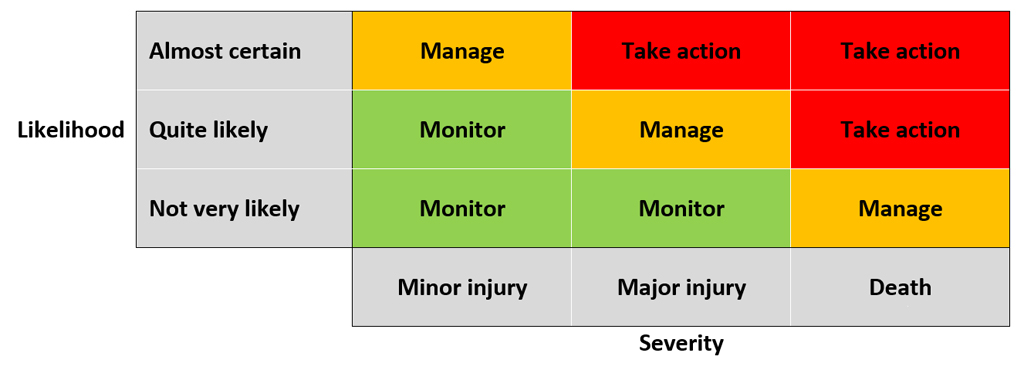

Q is for Quantitative Risk Assessment – it’s not quantitative just because you put numbers on categories.

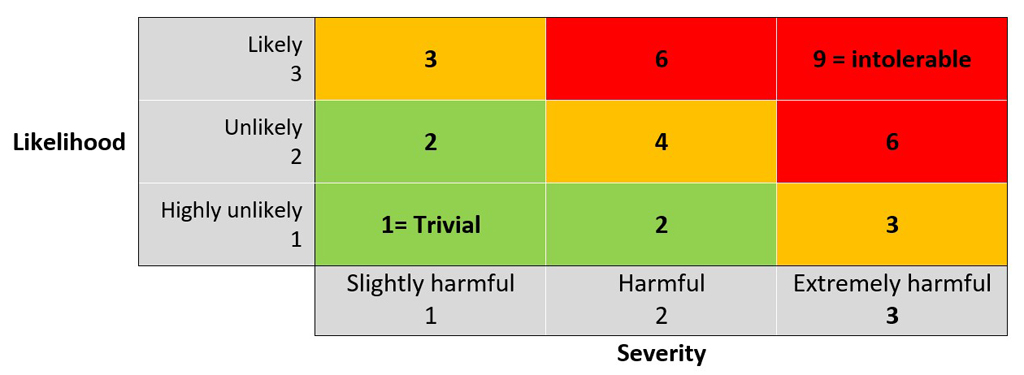

Used in IOSH Blueprint although the coloured grid was omitted in some versions. The grid below should come a lot earlier in the article that it does on the magazine article, so as well as the missing para I reproduced the following paragraph and my illustration:

On an OHS-related LinkedIn forum, an expert explained to a risk assessment newbie that a quantitative risk assessment was one where numbers are assigned to likelihood and severity, on a scale of say 1 to 3 or 1 to 5, the numbers are multiplied, and the result gives you a quantitative assessment of the risk.

In case it needs saying, this is not a quantitative risk assessment. It does not even deserve the title “semi-quantitative.” It is a qualitative risk assessment, where numbers have been used to prioritise and aid decision making. The same result could have been achieved without ever thinking about numbers, using a simple coloured grid:

A fully qualitative risk matrix - see, no numbers needed to get to the result!

TLDR: the LinkedIn expert was wrong.

My original article used an example relating to money rather than weight, so don’t read anything into that (other than perhaps the magazine’s desire to appear more European).

I have since wondered if the term ‘quantified risk assessment’ is a better choice that ‘quantitative’. Let me know what you think.

Q is for Questions

Missing introduction:

There are many situations where safety and health professionals need to ask questions. From interviewing potential recruits, through safety conversations and audits to accident investigations, the right question, asked in the right way at the right time, might provide the crucial information. The wrong question, or one asked tactlessly, can cause someone to clam up or provide a misleading answer.

R is for Risk homeostasis – can we really compensate for improvements in risk the way a thermostat compensates for a warmer day?

Missing introduction:

In his 1879 publication Notes on Railroad Accidents Charles Francis Adams describes how a rail company chose not to implement a block protection system because it feared that “those in charge of trains and tracks, who have been educated into a reliance upon it under ordinary circumstances, will, from force of habit if nothing else, go on relying upon it, and disaster will surely follow”.

R is for Risk Matrix – the perils of using a risk matrix for non-quantitative risk assessments.

Please note that despite the points made in this article, and in Q is for Quantitative Risk Assessment, the example matrix in this article was then mislabelled in editorial as “Basic quantitative matrix”! It is not. The missing intro is:

If we could assign a precise value for likelihood, such as 1 in 100 years or 1 in 10,000 events, and we could quantify the severity of all harmful outcomes on a single measure, such as loss of quality-adjusted life years, or a monetary value, we would not need a risk matrix. The risk associated with each hazard could be calculated and compared with set values, and we could determine that it was a trivial, manageable or unacceptable risk.

A qualitative risk matrix with labels that happen to be numbers

S is for Safety II – the noise about ‘new safety’, and why it isn’t new.

The final article published is a more ‘toned down’ version of what I think about Safety II and Safety differently. And in the years since I wrote it I am more and more convinced that while it might be a new way of nudging people towards managing people better, with the value of health and safety incorporated into decisions, it isn’t a new way of thinking. I worked with people at the start of my career in the 1980s who had been thinking like this (without making safety a separate discipline) since the 1960s.

The Eurocontrol reference for Professor Hollnagel’s work no longer works, but you can read similar ideas in A tale of two

safeties and Safety I, Safety II written by Hollnagel for the NHS). You can read and watch Professor Dekker on his own website. I’d also like to give a plug here for The Safety of Work podcast by Drew Rae and David Provan and Carsten Busch’s website. I find more inspiration from these sources around improved approaches to health and safety.

Missing introduction:

With Safety-I (traditional thinking) we define safety as the condition where nothing goes wrong – there is no loss of life, no injuries, no damage. The focus of safety practitioners is on hazards, horrors and harm – the opposite of safety. To improve safety, we look at where there is a lack of safety – accidents – and work from there. This negative approach has been applied to occupational health too – health surveillance looks for signs of harm, and investigations determine why someone suffers hearing loss or dermatitis.

S is for SRK – Skill Rule Knowledge

Missing introduction:

Forty years ago the Danish engineer, Jens Rasmussen published his SRK framework, distinguishing between skill-based, rule-based and knowledge-based behaviours.

S is for Sensible – see notes under T is for Triviality.

S is for Significant – see my longer article What is significant?

T is for THERP – looking at how techniques like THERP and HEART are used to make judgements about the likelihood of human error. Missing first line reads

Imagine there are two identical buttons on a machine. The one on the right switches it on, the one on the left switches it off. The operator knows this because they have been trained.

T is for Triviality

Missing introduction:

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations require employers to make a suitable and sufficient assessment of risks to health and safety, and to document ‘the significant findings of the assessment.’

The FAQ referenced in the article is no longer on the HSE website (they took away the whole of a very useful FAQ section that I often referenced). The word significant is used on the HSE website multiple times, but in most cases without much guidance. I’m not sure what ‘sensible risk’ is supposed to mean, but the explanation that follows is possibly more helpful than the original FAQ.

Sensible risk: A sensible approach to health and safety means focusing on the significant risks – those with potential to cause real harm and suffering – and avoiding wasting resources on everyday and insignificant risks.

In 2013 I wrote a longer article What is significant? This used case law to unravel significance and triviality. I presented on the same topic for the IOSH Metropolitan branch in 2014.

The scale below wasn’t used in the magazine article, but was my attempt to rank some of the terms used in legal cases.

U is for Underlying causes – are distinctions between root and underlying causes still useful in incident investigation?

The missing first line should read:

In C is for Causality we questioned the nature of causality. When Fred trips on building materials across the path while making a phone call, did the obstacle cause the trip or was Fred’s inattention the cause?

U is for Unsafe acts and conditions – are Heinrich’s precursors still useful?

Missing introduction:

The terms “unsafe acts” and “unsafe (mechanical or physical) conditions” appear in Heinrich’s Industrial Accident Prevention as the central domino in his accident sequence. Between the 1941 edition and the 1959 editions, the list of unsafe conditions grew, so that each list had 9 items (summarised in Table 1).

I provided two tables (old and new acts and conditions), but only one combined and abbreviated table is used on the IOSH Magazine website. I can recreate the tables here if there is any interest.

See also the more detailed article on Heinrich’s accident triangle. You might be surprised at my conclusions.

V is for Vicarious liability – where foreseeability and practicability won’t help.

Missing introduction:

When we considered G is for Guilt the situation

where Burglar-Bill knows immediately that he is guilty of breaking into a property was compared with the position of an employer who will be unsure of the guilt of the organisation until the facts have been considered in more detail.

V is for Violations – causes and cures

Missing introduction:

In J is for Just Culture, the definition for the term was given as ‘a culture in which frontline operators and others are not punished for actions, omissions or decisions taken by them which are commensurate with their experience and training, but where gross negligence, wilful violations and destructive acts are not tolerated’.

W is for Worker involvement – how to meet this requirement in ISO 45001.

Missing introduction:

One of the requirements of ISO45001 is for top management to ensure ‘the organization establishes and implements a process for consultation and participation of workers’ in the occupational health and safety (OH&S) management system. A previous (draft) version of the standard (DIS1, 2016) expected management to demonstrate that they were ‘ensuring active participation of workers, and where they exist, workers’ representatives.’ Perhaps the change reflects that, as with horses and water, workers can be invited to the table, but cannot be made to participate.

W is for WYLFIWYF – Why we get what we look for in investigations

In this case the introduction is not missing, but whoever typeset the text (not surprisingly) didn’t understand the code example I’d given:

Younger readers will take this for granted but before WYSIWYG, word processing was almost a programming job. For example, to print ‘Hello World’ your screen might show ‘\begin\bfHello \itWorld \end’.

The idea was that to make text bold when it printed you had to type \bf before it, and to make it italic, \it. You couldn’t just select the text and select ‘bold’ from a menu.

Horses led to water - some will drink, others won't

X is for Xpertise (and Y is for You) – competence and expertise, and what You need to do about it

Missing introduction (the uppercase Y for You was deliberate; I apologise for the use of X for Xpertise – if you have any better suggestions please let me know!):

Are You a health and safety expert? Type “expert health and safety advice” into a search engine, and you’ll get thousands of hits. However, the legislation and the HSE more commonly use the term “competence”, stretching as far in the HSE guide Getting specialist help with health and safety to “specialist help”, but never referring to “experts” or “expertise.”

X is for generations XYZ – busting the view that you can generalise about generations

No missing introduction, but I continue to be frustrated about the perpetuation of the myths.

Experience doesn't necessarily equal expertise, and you can't assume someone's ability or taste from their 'generation'

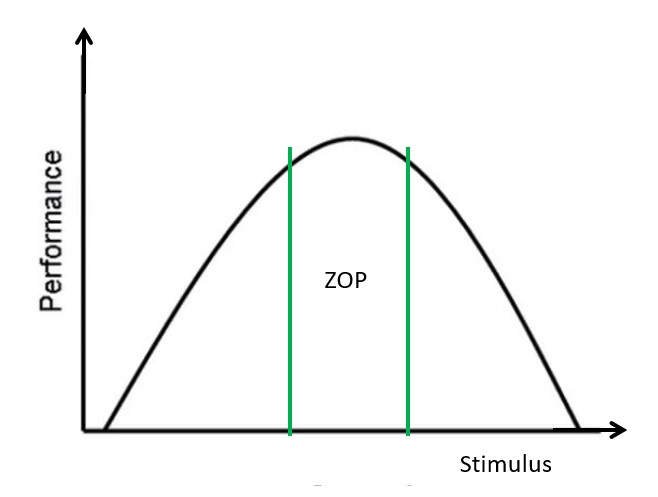

Y is for Yerkes-Dodson – understanding the stress response to stimulus

Nothing missing in the introduction, but I’m not responsible for the term ‘in these uncertain times’. I’d like to know if there was a time in history when people ever were certain. My Irish great-grandparents weren’t certain they’d be enough food to eat each week. My original introduction was:

Stress is very much on the agenda for health and safety professionals, as conference programmes and the rise in mental-health first-aid training demonstrate.

Read the article to see what "ZOP" stands for

Z is for Zeigarnik effect – why we remember things left unfinished, and how to use this effect in safety

This was inspired by the BPS Lexicon, although with a completely different emphasis. After writing this I discovered a further example of the application of Blyuma Zeigarnik’s work. She deserves a lot more recognition for this work.

Z is for Zero harm – looking at both sides of the argument.

Missing introduction:

The vision of zero harm is one where no one (staff, customers, contractors, public) has an accident or suffers a disease or illness because of work. Those advocating zero harm argue that this is the only target an organisation should set.

One question I raise in the article which is never answered by people talking on this topic is this:

- Does the rhetoric of zero harm miss an essential truth, unpalatable to some – that as a society we do accept a level of risk for a societal benefit?