Chapter 5: Assess the risk

5.1 Here's the theory

Early versions of the five steps included assessing the level of risk as part of step 3:

Evaluate the risks and decide whether the existing precautions are adequate or whether more should be done. (INDG 163, 1998, 1st edition).

Evaluate the risks and decide on precautions (INDG 163, 2006, 2nd edition and 2011, 3rd edition).

Evaluate the risks. (INDG 163, 2014, 4th edition)

It was clear from the editions up to 2011 that the HSE saw this as two steps, and there was an implication that the steps were carried out in this order: evaluate (or assess) the risks, and then decide on the precautions (controls). The 2014 version omits the need to control risk from any of the headings – criticism the HSE presumably took on board for their next version. In 2019, having combined the first two steps into one as explained in Chapter 4, the original step 3 was split into two steps:

- Step 2: Assess the risk

- Step 3: Control the risk

How then do we assess the risk?

5.1.1 SFAIRP and ALARP

So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable (SFAIRP) and As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP) form the basis of understanding what it means to “assess” the risk. See the box for an explanation if you aren’t familiar with the terms. We’ll look at the term again in Chapter 11 in the context of controlling risk.

Box 5.1: SFAIRP and ALARP

Sections 2 and 3 of the Health and Safety at Work Act require employers and the self-employed to ensure the health and safety of employees and others “so far as is reasonably practicable”. Other legislation, including that on lifting equipment and work equipment provision, includes the requirement to reduce risks to “as low as reasonably practicable”. Although SFAIRP relates more to the control of risk (that is, you must put controls in place SFAIRP) while ALARP relates to the assessment of risk (you must assess the risk to know that it is ALARP), the HSE regards ALARP and SFAIRP as equivalent, so you need to be familiar with both terms, and in particular the shared concept of what is “reasonably practicable”.

In his 2011 review Reclaiming health and safety for all, Professor Loftstedt noted that respondents had “overwhelming” supported the SFAIRP qualification in much of health and safety legislation because it allows risks to be managed in a proportionate way. He added, however, that there was “general confusion” over what it means in practice.

5.1.2 Reasonably Practicable

The definition of “reasonably practicable” comes from the Court of Appeal judgement in the case Edwards v. National Coal Board (1949). Lord Justice Asquith explained:

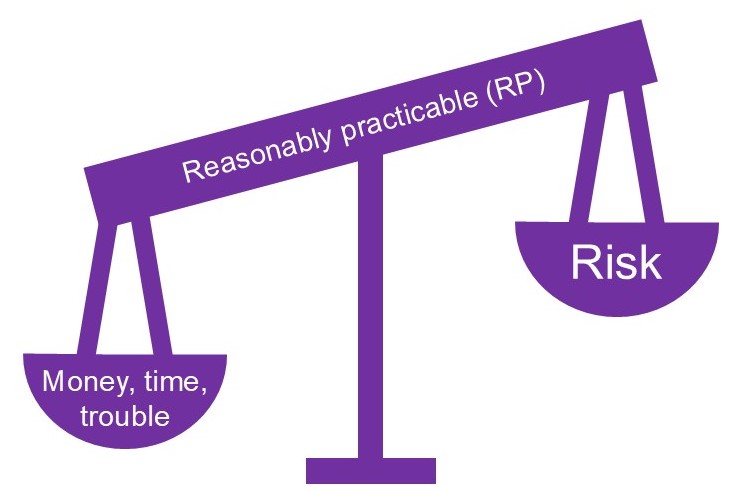

‘Reasonably practicable’ is a narrower term than ‘physically possible’ … the quantum of risk is placed on one scale and the sacrifice involved in the measures necessary for averting the risk (whether in money, time or trouble) is placed in the other, and that, if it be shown that there is a gross disproportion between them – the risk being insignificant in relation to the sacrifice – the defendants discharge the onus on them.

This is not a simple cost-benefit analysis – as Figure 5.1 shows, the scales do not balance. The owner of the risk (the duty holder) needs to show that there is “a gross disproportion” between the risk and the cost of avoiding a harmful outcome. Lord Justice Asquith didn’t say “if it costs a bit more to avert the risk than you think it’s worth..” He placed the onus on the employer to protect, unless the cost, time and effort is grossly disproportionate. We will look at what “grossly disproportionate” means in more detail in Chapter 12.

5.2 Why the theory doesn’t work in practice

5.2.1 Assessment and control are not discrete steps

Although the HSE separated assessment and control, the description of the “assessment” step from the HSE suggests that the authors don’t see a clear division between assessment and control.

Ask yourself:

Once you have identified the hazards, decide how likely it is that someone could be harmed and how serious it could be. This is assessing the level of risk. Decide:

- Who might be harmed and how

- What you’re already doing to control the risks

- What further action you need to take to control the risks

- Who needs to carry out the action

- When the action is needed by

Which steps does each bullet relate to? Are any unambiguously about “assessing the level of risk”?

Let’s review these bullets.

‘Who might be harmed and how’ was something we already considered in Step 1 – we had to do that to identify our list of hazards. The remaining four steps all seem to be related to control rather than assessment. The only bit of this step that sounds like it is entirely assessment is in the introductory sentence ‘decide how likely… and how serious’.

Whether expressed as two steps, or as a single step with two components, I don’t think the HSE ever intended that the processes should be discrete.

In the original ACoP for MHSW regs (L21, withdrawn in 2013) there is advice that:

In some cases employers may make a first rough assessment, to eliminate from consideration those risks on which no further action is needed. This should also show where a fuller assessment is needed, if appropriate, using more sophisticated techniques.

Just as I argued that identifying a hazard, and identifying who could be harmed are not discrete steps, so it should be clear that assessment is not a separate, one-off activity.

5.2.2 You assess at every step

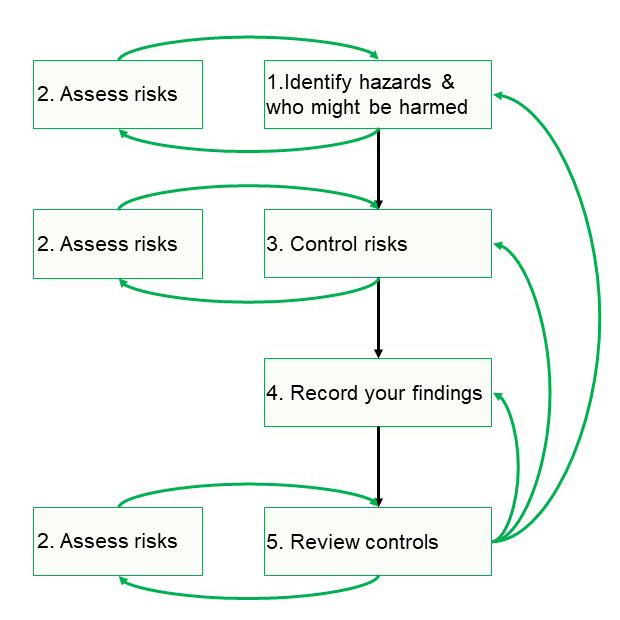

When I first learned about the process, it bothered me that it is called “risk assessment”, rather than “risk management.” The purpose of the process is after all not merely to assess the risk, so we know how dangerous or safe something is, but to manage the risk down to an acceptable level. But assessment comes into every step, as I’ve attempted to show in Figure 5.2:

- To identify something as a hazard, you assess if there is a significant risk. If the risk is trivial, you dismiss the candidate hazard. You decided that walking across the car park was unlikely to lead to an alien invasion, but that it could result in a trip on the curve, or a collision with a vehicle.

- In considering who can be harmed, you assess the risk to different types of people.

- In deciding if more controls are needed, you assess what you think the risk is with and without those controls. Every control you might add involves a further assessment of the risk, even if you are not consciously doing this.

- In deciding what to document, you consider the risk of not writing something down.

- In reviewing the risk assessment, and the controls, you are re-assessing the risk, and should be asking ‘does my original assessment of the risk need to be adjusted?’

Risk assessment is an iterative process, with new hazards identified when you consider who could be harmed, and other hazards dismissed once you assess the risks. Whether shown as one or two steps, this was always going to be an oversimplification of a complex process.

5.2.3 'Reasonably practicable' involves assessment and control

Look again at the scales in Figure 5.1.

Ask yourself: How do the steps of “assess the risk” and “control the risk” map onto these scales?

On the left side of the scales, we can list some possible controls, and estimate the financial cost, the time required, and the trouble needed for each possible control.

On the right side of the scales we have to assess the risk before a control, choose a control, then reassess the risk. You need to compare the change in risk from each possible control to determine its practicability.

5.2.4 Some controls can't be assessed away

Although Figures 5.1 and 5.2 suggest that controls are always determined by risk assessment, this is not always true. If you’ve identified that a hazard is relevant to your organisation, there are some controls you will need, regardless of your personal assessment of the risk or the benefit of a given control. Some controls are required by law. For example:

- If you have asbestos in a property, you must have an asbestos management survey to show the location and status of the asbestos. Even if it turns out to be very low risk (in excellent condition in a basement no one ever uses).

- If your workplace is noisy, there are levels of noise you must not exceed.

- If you have toilets, it must be possible to ventilate the facilities.

5.3 How can it be better?

My decision about which order to present the next few chapters was a compromise. A structure that constantly returned to assessment of risk would be difficult to follow, so the next few chapters are organised around a simplification of the process:

Chapter 6: One of my shortest chapters (so far) this covers mandatory controls which must be in place, regardless of your evaluation or assessment of the risk.

Chapter 7a: The theory of risk assessment, probability and numbers

Chapter 7b: What’s wrong with risk assessment (mostly a critique of the use of risk matrices)

Chapters 8, 9 and 10: How to assess the risk (with the knowledge that you will already have some controls in place, but might need more).

One reason for this simplification is that for straightforward risk assessments, you do not need to get bogged down with complex assessments. You know what you need to do, and if it is straightforward to make things safer, you should do so. The benefit of your risk assessment will come from your controls, which we look at next.

You can use the Contact form to send me feedback. If you’d like to receive an email when I add or update a chapter, please subscribe to my ‘book club’

Alternatively, you can go back to the book contents page.